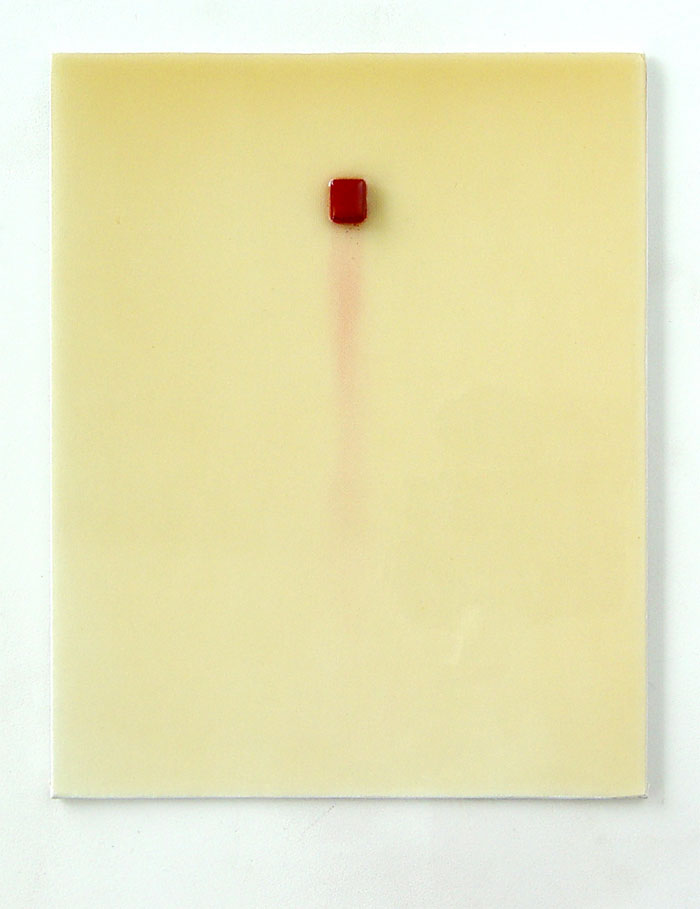

TWAN JANSSEN, Stage Property # 97118: “Untitled goodwill multiple”, 1997

30 x 24 x 1 cm

block of aquarel paint, enamel

edition 5, here nr 2/5

signed, dated, numbered

published by the artist

Collection K. van Gelder, Amsterdam

Twan Janssen – Inside the Art World

“In the past decades, the art world has met with increasing interest from philosophers and sociologists. Whereas the art world (galleries, museums, critics) used to be regarded as a mere vehicle for great art to be created and made public, it is now studied as such. Starting in the 1960s, philosophers like Arthur C. Danto and George Dickie theorized on how (factions within) the art world decided what is art and what is not; it was an attempt to develop an institutional theory of art as an alternative for old definitions of art. [1] According to the institutional theory of art, something is art when the art world decides that it is art; no more can be said about the ‘essential’ characteristics of works of art. In this theory of art, ‘the art world’ was used as a philosophical abstraction, but in the 1980s and especially the 1990s there was more and more sociological research into the workings of the art world. Especially influential was Pierre Bourdieu’s investigation of the literary world as a social ‘field’ with different factions, progressive or conservative, small and elitist or more mass-oriented. [2]

It was not only in the area of theory that the art world was explored. Artists themselves have been active in this regard as well. In the 1970s artists like Hans Haacke made works that criticized the art world and its ties to corporate capital (sponsors or trusties of museums were exposed by Haacke as ruthless exploiters), whereas in the 1980s artists took a less militant, more ironic view at their own world: Belgian artist Guillaume Bijl created a show with work by four young American artists, all of them fictional – a comment on how young ‘talents’ are hyped by the market. Twan Janssen is therefore far from being the first artist to take the context of art as his subject, but he is unique in treating the art world as a stage, himself as a player, and the works of art as props. In his work, fact and fiction intermingle, a career turns into a drama (or a farce, or a soap opera), and exhibitions become stage sets.”

Plays and Props

In 1996, Twan Janssen gave a talk entitled Lecture in Pasadena (California). The talk, which was in Dutch, was translated into English by an interpreter. Gradually, the translator’s text differed more and more from Janssen’s Dutch text. When it was finally time for questions from the audience, the interpreter completely misrepresented both the audience’s questions and Janssen’s answers to the other party. [3] It was a carefully planned performance, which was not so much an exercise in mocking the audience but an absurd little play in which everyone participated in the creation of confusion (the audience unknowingly, Janssen and the interpreter knowingly). While it was first and foremost a good prank, it can also be seen as an allegory on the relationship between artist, the media (the interpreter) and the audience. The artist attempts to control the diffusion and reception of his work, but in Lecture, this seems to be a rather doomed attempt, with the process of signification getting completely out of hand. Nonetheless, as it is all planned, the artist in fact asserts his control. For Janssen, who cannot stand wrong information about his work being passed on in the press, this might almost be an exercise in exorcism.

On the other hand, Janssen himself creates confusion by turning himself into an almost fictional character. Janssen plans his career in advance, which results in differences between plan and reality. Gallery owners and museum curators may get letters in which Janssen informs them that his career plans for the year in question demand that he has an exhibition in their institution. Understandably, these people do not always take on the offer, so new fictions have to be created to keep up appearances: in 1999, Janssen recreated the Paris-based gallery Air de Paris in a Museum in Schiedam (the Netherlands), because having a show at Air de Paris was one of his goals for 1999. Even though the gallery had nothing to do with this exhibitions, it received the usual percentage for works from this show that were sold. Another example of Janssen’s bizarre kind of career management is his exhibition Folly at Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam in 1997, wich contained a hilarious exchange of letters between Janssen and Sjarel Ex of the Centraal Museum in Utrecht; in this show, Janssen also presented letters to critics, who were warmly invited to write articles or make TV-items about the show. But Janssen is not an artist who is engaged only with strategies, and Folly did not consist primarily of texts on pieces of paper. These texts were comparatively small elements in an installation that consisted of paint in all kinds of shapes and forms: there were objects that might qualify as paintings, but there were also sheets of paint dangling from the system of chrome tubes which Janssen had installed in the gallery space. Janssen uses acrylic paint as a material that can be used in lots of ways, to make sculptures, reliefs, objects. The works of art, called Stage Properties, are combined in exhibitions to form installations that are like sets for plays or television shows.

In his famous series of Artforum articles called ‘Inside the White Cube’, Brian O’Doherty has analysed how artists have increasingly used the white space of the modern art gallery or museum as a constituent element of their work rather than just as a space in which to show self-contained works of art. [4] This has led to the rise of environments and installation art since the 1960s, in which the work of art takes possession of the gallery space. This has made art more theatrical, as one does not contemplate an isolated work of art anymore but rather walks through the work of art like an actor in a stage set. [5] But if much contemporary art is theatrical in nature, Janssen is much more explicit about this than most. He turns the work of art into a ‘stage props’ as if they were objects on the set of a play or a TV show; Janssen’s show Folly had numerous TV-references, including a ‘blue box’ that could be used for chromakey effects, and a theme song, Twan’s Theme. By giving his works titles like Untitled (Stage Property # 96018), the glorious work of art, an object of veneration and economic interest, is equated to objects that play a merely functional part in sets for the theatre or television. These works of art are thus ‘outed’ by Janssen as being not cult objects in an art-for-art’s-sake religion, but props in a social theatre, in the gallery or in a collector’s home, in the soap opera of our lives.

Janssen’s 1996 exhibition Solo at the Museum voor Moderne Kunst in Arnhem consisted of a set for a play which was also called Solo; the set consisted of a gallery with some works of art in it, and next to this there was a wardrobe and all kinds of other objects needed for the production of the play. The play itself – which was not preformed but published as a book – was about a young artist called Twan Janssen, who has his first exhibition in the gallery of the fictional Rienk Kamps. [6] This comic play is reminiscent of Dutch artist and comedy-author Wim T. Schippers – whose regular composer Clous van Mechelen composed Twan’s Theme for Folly. In Solo, like in Schippers’s television shows, radio programmes and plays, the characters are unable to really communicate with others, absorbed as they are by their own silly preoccupations and by their desire to appear clever and on top. The interplay of this egotistical cast does not lead to a happy ending: the fictional Twan’s show is a commercial failure, and because of this the gallery owner loses his interest in Twan’s work. For the real Twan Janssen things have worked out differently, but he still feels the need to will himself a career by making it up beforehand. Even more than a witty take on today’s art world with its career-mindedness, this looks like an attempt at practical magic, as if wishes might charm reality into complying with them.

Presents and Parties

One of the most successful ‘formats’ which Janssen has developed in recent years is that of small canvasses (usually white) that are wrapped with a ribbon of acrylic paint, which is tied with ornamental curls. Instead of being used to form a composition on the canvas, the paint is used as material to wrap the canvasses up as gifts. The result is both witty and beautiful. Art is presented here as a luxury, as an alluring commodity which might make a nice (expensive) gift for one’s loved ones. These pieces are both alluring and, so to say, meta-alluring. The term ‘stage property’ is in fact much too modest for such works; they have clearly been created with such care that they are more than that. But they are also something different than ‘normal’ luxury goods: while Janssen reflects the fact that art is a commodity and the art world its market, he also suggests that this commodity might still differ in some important ways from other commodities.

According to Marx’s description of ‘commodity fetishism’, commodities seem to engage in ‘social’ relations with one another, their prices seemingly resulting from their relations to other (more or less expensive) goods. [6] Marx stated that this is an illusion (the illusion of commodity fetishism), because in fact the prices result from the amount of labour invested in the production of the commodity, not from the exchange value of goods on the market. Works of art can be seen as the ultimate commodity because their prices are often (especially in the case of famous artists) completely unrelated to the costs of production; if the aura of the artist is strong enough, prices can be immense. In his monumental theory of aesthetics, Theodor W. Adorno has elaborated upon the relationship between modern works of art and other commodities. Adorno realized that when the work of art is made for art’s sake, without a specific social purpose, it turns into the ultimate, free-floating commodity, but he also stated that since “the magical fetishes are among the historical roots of art”, works of art may still be tied to some form of fetishism which “transcends commodity fetishism”. [7] The term fetishism was of course derived by Marx from the religious practice of fetishism which had been studied by western observers in Africa, where certain objects (fetishes) were regarded by the believers not as dead objects but as the seat of some deity or spirit. Even in commodified modern and contemporary works of art, something of this ancient magic may according to Adorno still remain. Like in the case of ‘primitive’ fetishes, human fears and desires are projected on the work of art, which seems to become a living entity.

Career-minded as he is, Janssen might be expected to rejoice in the commodified status of the work of art – which has only become more pronounced since Adorno’s day – and work within its limits. Still, his enticing commodities can be seen to regress to a status where the object becomes something that has a life of its own. Janssen’s works sometimes take the form of little bachelor machines that seem to be completely-self contained: Five Small Creative Dips (Stage Property # 79091) from 1997 consists of metal sticks being dipped into cans of paint; they are hanging from wires that are automatically lowered and then raised again. As a result, the sticks collect more and more paint and turn into small paint sculptures. Funny and absurd as such a piece is, it also makes clear that Janssen’s works are far from being mere ‘stage props’. In this case, the work rather seems to consist of ‘actors’ that perform a futile play. The objects are animated, as things might appear to be animated by a god or spirit to a practitioner of ‘primitive’ fetishism – or to someone under the spell of commodity fetishism, the two becoming all but indistinguishable. But Janssen’s works do not have to be animated in a literal sense to have this kind of effect: his ‘gift-paintings’ are for instance animated by the fact that gifts are charged with human hopes and fears that are externalized by the subject. Sometimes hints of melancholy make themselves felt in these pieces, especially the more ornamental and refined ones, where a lot of labour seems to have been spent in order to create something splendid enough to fill some kind of void. After all, presents and ribbons are not only associated with festive occasions, but also with disease. Gifts and tragedy have an intimate relation. Even if gifts are or have been commodities, once they attain the status of a present they partake in a different (psychological) economy. In such works, the artist and his schemes took a step back in order to leave the stage to objects that are hovering somewhere between the status of stage property, ultimate commodity and a primitive fetish.

In 1998, Janssen presented the exhibition Big Boy Now at Galerie Van Gelder. On this occasion, Janssen’s mastery at playing with the art world once again showed itself: the invitation card mentioned that there was no official opening (rather unusual for a gallery show), but there was a second version of this invitation for a smaller group: this card mentioned that while there was no opening, Twan would celebrate his thirtieth birthday at the gallery on the evening when the opening would normally be. After this party, the installation was far from being jubilant. Two monitors showed video images of an abstract landscape of paint, which was reminiscent of Caspar David Friedrich’s painting of an ice sea: a bleak, lifeless landscape. The acrylic festoons and buntings which dangled from the walls and ceiling were a rather sad sight without any human presence, except for the solitary viewer’s. This was not a failure on the artist’s part, but rather a subtly created atmosphere. One of the festoons consisted of a string of small red ribbons moulded from paint; as these had the form of the ribbons that are worn by people who want to raise money and / or consciousness for the fight against AIDS, Janssen had forged another link between decoration, disease and death. The paint festoons, like the gift paintings that were lying on a shelf, were in this settings sign of absence rather than presence. If they were animated fetishes it was what was a feeling of absence that animated them – the ghosts of departed people, parties that are merely memories now.”

Sven Lütticken

Notes:

[1] A critical analysis of Dickie’s institutional theory of art is given by Karlheinz Lüdeking in his Analytische Philosophie der Kunst, Frankfurt am Main, Athenäum Verlag, 1988, p. 157-193.

[2] Pierre Bourdieu, Les règles de l’art. Genèse et structure du champ littérair, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 1992.

[3] Extracts have been published in: Twan Janssen, ‘Lezing / Lecture’, Kunstlicht 19 (1998), nr.1, p. 29-32.

[4] Brian O’Doherty, Inside the White Cube – The Ideology of the Gallery Space, Santa Monica / San Francisco, Lapis Press, 1986. (The articles were originally published in Artforum in 1976.)

[5] In his article ‘Art and Objecthood (published Artforum in 1967) Michael Fried waged war against the intrusion of ‘theatre’ into visual art, especially in the guise of Minimal art. However, Fried’s hysterical diatribe against ‘theatrical’ art did not prevent the rise of ever more theatrical visual art. ‘Art and Objecthood’ has been republished in: Michael Fried, Art and Objecthood, Chicago / London, The University of Chicago Press, 1998, p. 148-171.

[6] Twan Janssen, Solo. Een toneelstuk in vier bedrijven, Amsterdam, Galerie Van Gelder Editions, 1995.

[7] “Sind die magischen Fetische eine der geschichtlichen Wurzeln der Kunst, so bleibt den Kunstwerken ein Fetischistisches beigemischt, das dem Warenfetischismus entragt.” Theodor W. Adorno, Ästhetische Theorie, Frankfurt am Main, Suhrkamp, 1970, p. 338.